Mick Archer

Mick Archer is a journalist who has written extensively about AT including as Editor of Special Children Magazine and Special World.

“Every cloud has a silver lining, or so the optimists say. An unexpected invitation to attend ATIA 2021 seemed like the perfect opportunity to test the proverb out”.

ATIA 2021

Every cloud has a silver lining, or so the optimists say. An unexpected invitation to attend ATIA 2021 seemed like the perfect opportunity to test the proverb out.

Here we were in the midst of a global pandemic, which is a cloud by anyone's definition. So how were students with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) being impacted and was assistive technology (AT) providing any relief.

I had been to ATIA before, in 2015. On that occasion it involved an eight-and-a-half hour flight from Manchester to Orlando. This time I would be attending ‘virtually’, thanks to the ubiquity of online meeting solutions.

But would it work?

Flexibility

A visit to ATIA’s website was enough to rattle any die-hard technology evangelist. In the physical world ATIA is an all-encompassing event with an extensive seminar programme, a major exhibition, a vibrant social programme and exhaustive (exhausting?) networking opportunities. What could possibly go wrong trying to replicate this online?

My initial assumption was that the virtual version would be a more modest affair, but that was quickly dispelled. On the conference website I was greeted by the familiar face of ATIA’s CEO, David Dikter, who confidently announced that ATIA 2021 would consist of “over 150 educational sessions, five different credentialing programs for CEUs [Continuing Education Units], an exhibitors experience as well as social activities”. The guiding principle was ‘flexibility’. Delegates were free to watch pre-recorded sessions, register for live ones scheduled over several days (25 January — 4 February) and revisit recordings at any time up until 23 June.

The 150 sessions were divided into four distinct strands: Augmentative & Alternative Communication (AAC), Vision & Hearing Technologies, Education & Learning, and AT for Physical Access & Participation. With 20 plus British AT Scholars attending this year’s event, I decided to leave the finely focused sessions to them and immerse myself in the Education & Learning strand.

I opted for four live sessions: two on each day of the Education &. Learning strand (27 January and 1 February). Everything was scheduled to take place between 12 noon and 4.00 pm Eastern Standard Time, which meant 5.00 pm to 9.00 pm for those of us this side of the pond.

My choices were ‘Integrating Digital Assessment Tools to Cultivate Tech-Empowered Remote Learners’; ‘AT Leadership in Virtual Schools: How have things changed?’; ‘The Assistive Technology Policy Landscape: Policy Adapting to a Global Pandemic’; and ‘Embrace the Pivot! Implementing an AT Service Delivery COVID Preparedness Plan’.

As the titles suggest my interest was in how SEND professionals had responded to finding themselves teaching remotely, in most cases without any prior notice. Each sessions lasted an hour and all were captioned. Space precludes a detailed account of each of them so here are just some of my key takeaways.

Takeaways

Resilience seems to be a 21st century buzzword, but after 30 plus years of interviewing SEND practitioners I knew that if anyone was going to rise to the challenge of remote teaching it would be them. By nature they are problem-solvers.

In my first session Megan O’Brien and Laura Vanderberg described the stress and dislocation experienced by teachers who left school one day unsure of when they would return. Separated from their students they had to retool and find new ways of working online, including carrying out normative assessment, the focus of their talk.

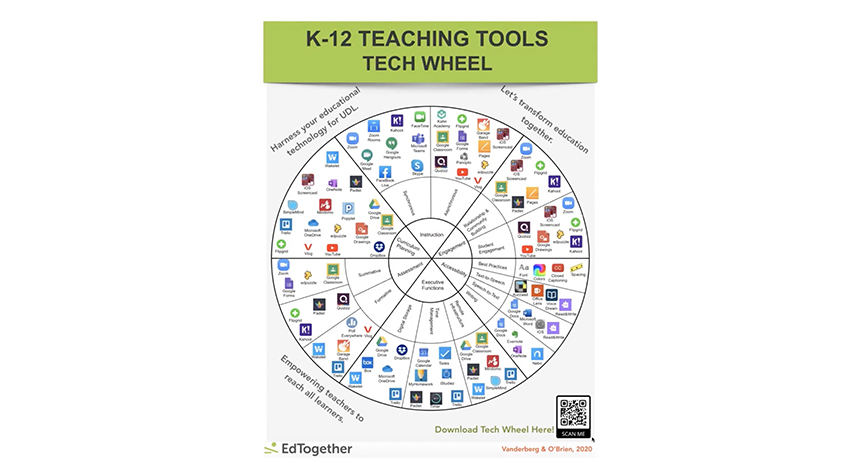

As a way of illustrating the possibilities they developed a ‘K-12 Teaching Tools Tech Wheel’, which brings together a host of online resources that teachers can use to tackle this and similar challenges when teaching remotely. Among the tools highlighted were Flipgrid, Padlet, Trello, Wakelet, Kahoot! and Quizizz. If you don’t know these then be sure to check them out.

A danger with any form of teaching, physical or remote, is that participants are treated as passive consumers while teachers impart ‘knowledge’. This is arguably a greater risk with virtual teaching as by minimising interaction teachers feel more in control of what is a fraught process. It was therefore good to see presenters modelling best practice, including team teaching and making full use of the interactive features of online meeting solutions such as Zoom’s ‘Chat’ as well as some of their own teaching tools such as Padlet.

Resilience was also on show in Oregon, from where Gayle Bowser and Penny Reed presented. Gayle and Penny emphasised that while the Covid pandemic has challenged AT professionals to develop new ways of working it has also created opportunities for them to change the attitude to AT of schools and fellow teachers. True transformation, they argue, has to go beyond asking what was done in the past and how it could be done better in the future to offering a vision of how things might look in say five years time.

Drawing on several sources, including the Mirage Report on teacher development, Peter G Northouse’s Leadership and their own Leading the Way to Excellence in AT Services, they walked us through a well-honed presentation on instigating and leading systemic change. This covered the basic leadership practices distilled by Leithwood, Harris, and Hopkins: building vision and setting directions; managing the program of change; understanding and developing individuals; and redesigning the organisation. Good pointers for responding to any crisis.

From a starting point of ‘do your best’ many US states quickly developed specific guidance on establishing and running virtual schools. Two good examples cited were the Continuous Learning Task Force Guidance issued by Kansas State Department of Education and Ensuring Equity and Access issued by Oregon. Importantly these now incorporates advice on returning to face-to-face teaching. UK practitioners would do well to compare these with the guidance provided by their own LEAs.

In my third session, Audrey Busch, the Executive Director of ATAP, and Marty Exline, Director of the AT3 Center, illustrated another great feature of ATIA: its capacity to update delegates on the implications for AT of recent political changes at national (federal) and local (state) level. For an overseas visitor a session like this may seem superfluous but learning from others is only enhanced by knowing something about the educational context in which they operate.

While a number of US Cabinet members influence general provision for those with SEND the key figure for many practitioners is that of Education Secretary where Miguel Cardona has replaced Betsy DeVos. A recent report in Education Week confirmed that prior to taking up office Cardona had met (virtually) with representatives from dozens of organisations to discuss disability issues, including the impact of Covid on access and funding and on future plans to address ‘instructional loss’.

The coordination between ‘disability’ organisations in the US and their impact on federal and state provision in terms of policy and funding is impressive; advocacy is well-organised and concerted. At the time of this presentation organisations were engaging with the US’s fifth Covid relief package — dubbed the American Rescue Plan — which was finally agreed this month (March). This includes $126 billion for schools of which $3 billion is earmarked for supporting students with disabilities. This allows for the purchase of AT.

Finally, I joined Barbara Welsford and Mike Marotta who also made use of Padlet, this time to get participants to record the positive things they’d experienced over the last year. Here, perhaps, was the clearest account of what teachers felt had changed for the better. Some wrote of greater parent and sibling interaction, others of colleagues no longer being able to say ‘I don’t do technology’, and still others of the secret pleasure of being able to access training from home.

We also learnt that the idea underpinning this session had been inspired in part by a series of virtual Town Hall discussions for AT professionals organised by the Richard West Assistive Technology Advocacy Center (ATAC) of Disability Rights New Jersey, where Mike is Director. These weekly ‘meetings’ continue to this day and previous ones are available on ATAC’s YouTube channel.

The fruit of this and further virtual collaboration — some of it international — was the Assistive Technology Service Delivery Covid Preparedness Planning Guide, a Google Slide presentation produced by the South Shore Regional Centre for Education in Nova Scotia where Barbara is an AT Specialist. This can be accessed online.

There were some inspiring experiences described in this session but one stood out for me: the use of online learners to mentor other online learners who were only just getting their heads around the tools being used.

Conclusion

In 2022 I have no doubt delegates will return to ATIA in Orlando and one of the big discussions will be about their experiences since they last met face to face. What’s equally clear is that there is a place for virtual events of this kind for those who can’t make the journey.

The lesson of lockdown is that creativity can thrive even in the darkest spaces so long as there are people determined to make things work. Maybe the optimists were right after all.